BY KHADIM ZAMAN

Debates about AI writing often circle the same questions: should a writer disclose that they used ChatGPT or another system? Is it plagiarism if an AI articulates your argument? Should transparency be required as a moral obligation or dictated by marketplace expectations? These debates are urgent but misframed. They assume that the words themselves are the unit of authorship, when in fact originality resides in the ideas those words convey. Copyright protects expression, but the real creative act is the crystallization of thought.

Words are vessels; ideas are the cargo. Writing achieves its human value not in syntax or vocabulary but in the originality of the thought. We still evaluate invention this way in other domains. Patents do not protect a particular diagram or description; they protect the novelty of an underlying concept. A machine could reproduce the diagram in another language, or a human could paraphrase it, and the invention would remain the inventor’s. Writing should be treated similarly.

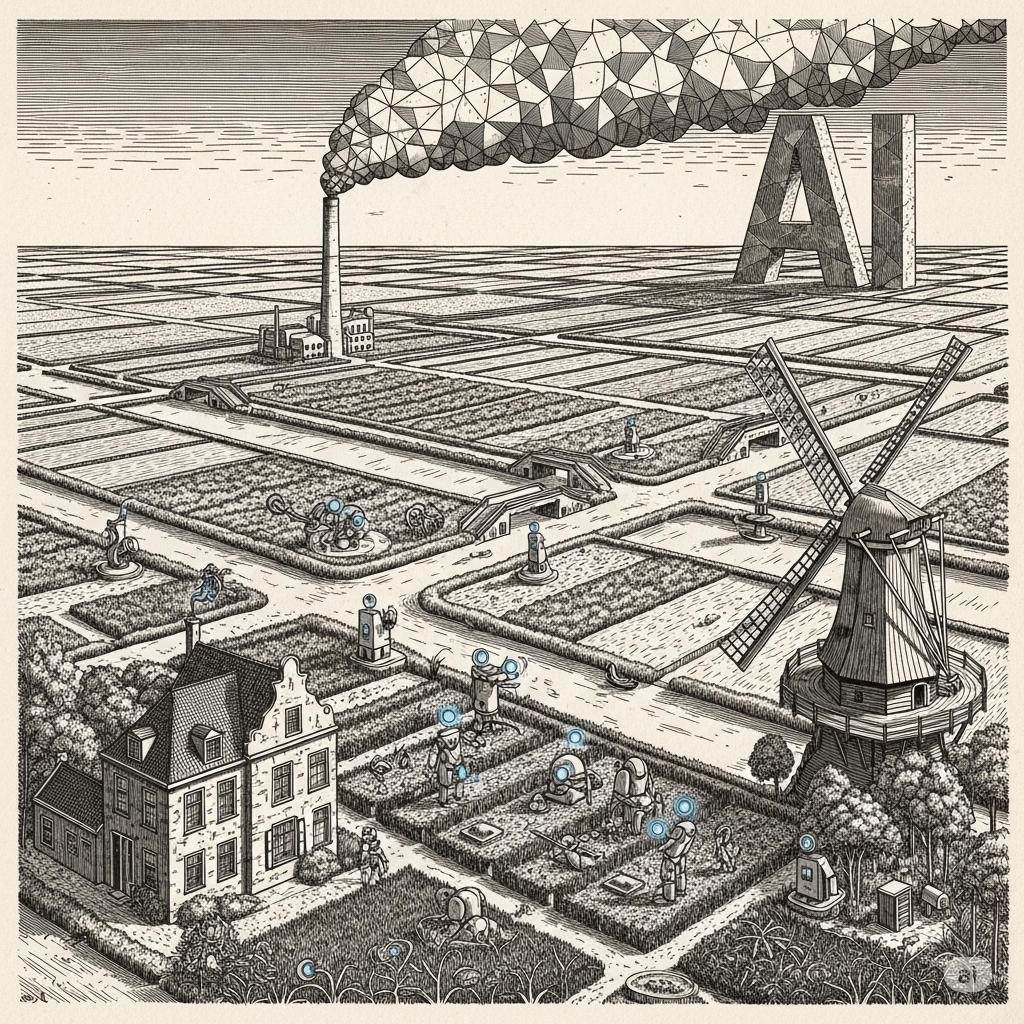

Current AI systems are not creators of genuinely new ideas. They synthesize, recombine, and polish the patterns of human thought embedded in their training data. If they could originate ideas, they would already be designing better versions of themselves, pushing us into the phase of recursive, hyper-intelligent AI. We are not there. For now, AI functions like a secretary or typist: it organizes, clarifies, and sometimes enhances our ideas, but it does not originate them. Consequently, using AI to articulate your thoughts is ethically unproblematic, just as a secretary typing Einstein’s equations does not claim credit for the science.

Not all writing is reducible to ideas. Poetry, lyricism, and other forms where the texture of language itself carries meaning cannot be outsourced without loss. But essays on political theory, scientific reasoning, or philosophy are idea-first forms. In these domains, to ask whether the AI arranged the words is as irrelevant as asking whether a secretary pressed the keys to complete a manuscript.

The challenge lies in measurement: how do we know whether a text contains originality or merely recombination? Here, the analogy of sprinting is instructive. In track, a runner who leaves the blocks too quickly is penalized with a false start. Even absent malice, a threshold exists: below a physiologically possible reaction time, one must have started early. Intent is irrelevant; what matters is whether performance crosses a defined limit. Writing could one day have its own threshold.

Most humans recycle ideas, consciously or not. Most AIs do the same. The rare originality is what matters. Future systems could detect it using a combination of semantic analysis, citation networks, and historical corpora—algorithms that assign scores based on the novelty of an idea relative to everything that has come before. In effect, originality would be quantified using an approach akin to Google’s PageRank: just as web pages are ranked according to the number and quality of backlinks pointing to them, texts would be ranked according to their relative novelty and connections to prior knowledge. Those texts rising to the top would be the ones that add something genuinely new to the intellectual ecosystem.

To make the system more realistic and equitable, we could add a second dimension: adoption over time, modeled on the diffusion of innovations. Originality alone would create a top-heavy ranking, where only rare ideas dominate. By incorporating adoption, texts can be recognized not just for breaking new ground but for influencing the intellectual ecosystem:

Synthesizers and Early Adopters: Writers who identify important ideas early, apply them in new contexts, or explain them clearly to broader audiences. Their originality may be moderate, but their adoption curve places them high in influence. Think Malcolm Gladwell or Thomas Friedman.

Bridge-Builders: Those who connect ideas across disciplines, making abstract concepts accessible. Adoption patterns differ across fields, so these works may be influential in multiple domains even if they are less visible in any single discipline.

Amplifiers: Writers who help emerging ideas reach critical mass, giving them visibility and resonance. Their work ensures that valuable ideas are adopted widely, even if not fully original.

A work’s influence evolves dynamically. Adoption curves account not only for early uptake but also delayed recognition—ideas that gain traction decades later—as well as ephemeral influence—ideas that initially seem important but fade quickly. Adoption could be measured through citations, references, practical application, or other forms of engagement, though safeguards would be needed to prevent manipulation, such as coordinated campaigns to artificially boost scores.

The system also applies to collaborative or team-authored work: originality and adoption metrics could evaluate the collective contribution while still recognizing individual influence within the team, though weighting methods would need careful design.

This two-dimensional ranking system reflects both novelty and influence, acknowledging that intellectual progress is a collaborative, temporal process. Writers who consistently produce original ideas or strategically adopt and disseminate valuable concepts are both recognized. Even highly original work may rank lower until adoption increases, while systematic early adopters can achieve influence even without generating new ideas themselves.

Some might object that ideas and language cannot be disentangled. True, meaning emerges through expression; ideas are rarely perfectly separable from their articulation. Yet in practice, separating thought from words is useful. It allows us to reward innovation rather than mere stylistic talent, to detect invention even in imperfect prose, and to focus attention on the human mind’s creative contributions. This is not a philosophical denial of language’s power, but a pragmatic framework for the age of AI-assisted writing.

Even if AI eventually becomes capable of producing original ideas, the same approach could adapt. Thresholds of originality and adoption could distinguish between human and machine insights, or between incremental and truly novel contributions, allowing society to value creativity without conflating the tool with the thinker. The principle remains: originality resides in the idea, not in the specific arrangement of words.

Old habits will die slowly. Copyright thinking is centuries old, and many still equate authorship with the arrangement of letters. But as AI becomes ubiquitous, words will become increasingly abundant while true ideas remain scarce. The future will reward those whose minds generate originality or strategically adopt and disseminate ideas, not those who merely assemble phrases. When that day comes, debates about AI disclosure will seem as quaint as early discussions about photography: anxious, urgent, but focused on the wrong question. Originality has always belonged to thought, and in the age of AI, we finally have the tools to recognize it.